Hokianga Heirloom Tomatoes

Glyphosate & Soil Health: What We're Learning

Let's take it from the beginning

Glyphosate has become a renewed focus of public discussion. In recent years, several scientific papers once relied upon to inform regulatory and management decisions have been withdrawn or re-evaluated after critical methodological errors were identified. As a result, parts of the evidence base that shaped earlier conclusions are now being reconsidered.

At the same time, advances in research tools and analytical methods now allow us to observe biological and ecological processes that were previously invisible. These developments have deepened our understanding of soil systems, microbial communities, and plant–chemical interactions, revealing impacts that earlier studies were not equipped to detect.

Together, these shifts invite a careful re-examination of assumptions that once felt settled. This is not a rejection of science, but a reflection of how science evolves — refining itself as knowledge, methods, and perspectives improve.

With that context in mind, this reflection explores glyphosate’s history, its adoption, and the growing questions surrounding its long-term effects. Let us begin.

"For gardeners, this matters not in theory, but in the living soil benath our feet."

Old Stories, Living Truths

I need to draw us back to creation — not because this story belongs to me, but because it belongs to all of us.

Across cultures and time, people have told stories about how life began. They differ in language and symbol, but they return again and again to the same elements: soil, water, breath, and relationship. These stories were not written to explain chemistry or ecology as we understand them today, but to remind us who we are, and where we come from.

""Ashes to ashes, dust to dust."

"By the sweat of your brow you shall eat bread, until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; for dust you are, and to dust you shall return." - Genesis 3:19In the biblical story, the first man is called Adam — a name drawn from the word for earth or soil. The first woman, Eve, carries the meaning of life or living. Together they express a truth older than theology: life emerges from soil, and soil is sustained by life. They are not separate things, but parts of an ongoing relationship.

This is not about belief or doctrine. It is about remembering connection — how our lives, our food, and our futures are bound to the ground beneath us. When we forget that relationship, our decisions change. When we remember it, they change again.

There is a sacred balance and if you would like to learn more I suggest David Suzuki with Amanda MacDonnell, " The Sacred Balance" rediscovering our place in nature. We are all connected.

From Reverence to Control

As knowledge grew, so did confidence.

The natural world, once approached with caution and respect, began to be understood as something that could be measured, predicted, and managed.This shift was not malicious. It was driven by genuine progress — advances in chemistry, biology, engineering, and agriculture that dramatically improved food security, reduced hardship, and supported growing populations. Problems that once required time, labour, and uncertainty could now be addressed quickly and reliably.

In this new framework, complexity was broken into parts. Systems were simplified so they could be controlled. Weeds became competitors rather than indicators. Soil became a medium rather than a living system. Success was increasingly measured by efficiency, yield, and uniformity.

Time horizons narrowed. Decisions were often evaluated over seasons or years, rather than decades. Effects that unfolded slowly — through soil processes, ecological relationships, or cumulative exposure — were easy to overlook when they did not register immediately.

Chemical tools emerged within this mindset. They promised consistency in an unpredictable world and relief from the relentless pressures of land management. For farmers, councils, and gardeners alike, these tools felt practical, modern, and responsible.

What was lost in this transition was not care, but relationship. When systems are reduced to components, the connections between them become easier to miss. This context matters. It explains why chemical solutions were embraced not as acts of dominance, but as expressions of optimism — a belief that with enough knowledge, nature could be brought into balance through control.

Why It Was Embraced

Glyphosate entered Aotearoa New Zealand in the mid-1970s, at a time when confidence in chemical solutions was high and their benefits appeared clear. Internationally, glyphosate had been introduced only a few years earlier, promoted as a highly effective, broad-spectrum herbicide with properties that distinguished it from many products that came before it.

In New Zealand, its arrival coincided with real pressures on land use. Farming systems were intensifying, forestry was expanding, urban councils were responsible for increasing areas of infrastructure, and labour costs were rising. Weeds were not a theoretical concern — they were an immediate, visible problem affecting productivity, access, and safety.

Glyphosate appeared to offer a practical answer. It was effective against a wide range of plants, worked systemically rather than by contact alone, and — crucially — was understood at the time to leave no residual activity in soil. This made it attractive for pre-plant “knockdown” use and for situations where repeated mechanical cultivation was undesirable.

Regulatory frameworks of the era reflected the scientific understanding available at the time. Assessment focused largely on acute toxicity, immediate exposure risks, and short-term outcomes. The longer-term behaviour of chemicals within complex soil systems, microbial communities, and ecological networks was not yet well understood, nor easily measurable with the tools then available.

Within this context, glyphosate was not adopted recklessly. It was adopted rationally, based on the evidence, needs, and values of the time. It aligned with prevailing ideas about efficiency, control, and progress, and it delivered tangible benefits in many settings.

What is important to recognise — and easy to forget in hindsight — is that glyphosate entered the story as a solution, not a controversy. The questions that surround it today emerged gradually, as scientific tools improved, systems thinking expanded, and attention shifted from immediate outcomes to cumulative and long-term effects.

What We Later Began to Notice

As glyphosate use became widespread and persistent, questions began to emerge — not suddenly, and not from a single source, but gradually, as scientific tools improved and attention widened beyond short-term outcomes.

Early assessments had focused largely on acute toxicity and immediate effects. Over time, researchers began to look more closely at indirect, cumulative, and system-level interactions, particularly in soils and ecosystems repeatedly exposed to herbicides.

One area of growing interest has been soil health. Soil is now understood not as an inert growing medium, but as a complex living system, shaped by microbial communities that play critical roles in nutrient cycling, plant health, and resilience. A number of studies have raised questions about how glyphosate interacts with these microbial processes, including whether repeated exposure may alter microbial balance or function in ways that are not immediately visible above ground.

Attention has also turned to plant physiology. Glyphosate is designed to interfere with a metabolic pathway present in plants and many microorganisms. While this mechanism explains its effectiveness as a herbicide, it has prompted further investigation into whether sub-lethal or indirect effects may occur in treated environments, particularly where applications are frequent or widespread.

Another area of concern has been resistance. Over time, reliance on a single mode of action has contributed to the emergence of glyphosate-resistant weeds in multiple countries. This has led to increased application rates, additional chemical use, or more complex control strategies — outcomes that complicate the original promise of simplicity and efficiency.

Human health questions have also remained part of the discussion. Regulatory agencies in different jurisdictions have reached differing conclusions about glyphosate’s risk profile, reflecting variations in assessment methods, evidentiary thresholds, and interpretation of epidemiological data. This divergence has underscored the challenges of assessing long-term, low-level exposure in complex real-world settings.

Across these areas, a common theme has emerged: what happens over time matters. Effects that are subtle, cumulative, or mediated through living systems are harder to detect, slower to confirm, and easier to dismiss when decision-making is framed around short-term indicators.

None of this means that earlier decisions were careless. Rather, it reflects the reality that scientific understanding evolves. As methods improve and perspectives broaden, questions that once sat at the margins can move closer to the centre.

This shift — from asking whether something works, to asking how it behaves within living systems over time — marks a turning point in how glyphosate is now being examined.

Ecology Meets Ethics

Ecology asks how living systems function.

Ethics asks how we ought to act within them.For much of the modern era, these questions were treated separately. Decisions about land, chemicals, and productivity were framed as technical matters — issues of efficiency, effectiveness, and control — while ethics was reserved for social or personal concerns. Increasingly, that separation no longer holds.

This is where the idea often described as the Green Imperative enters the discussion.

At its simplest, the Green Imperative recognises that when human activity has the power to alter living systems at scale — soils, waterways, ecosystems, and climate — ecological understanding becomes inseparable from ethical responsibility. It is not an ideology or a rulebook. It is a recognition that how things work must inform how we choose to act.

One reason this shift matters is scale and time. Human decisions now operate across landscapes and generations. Effects are often cumulative rather than immediate, and they may unfold slowly, below the surface, or far from where the original decision was made.

Humans are sometimes described as time-binding species. We pass knowledge, tools, and habits forward. We inherit the outcomes of past decisions, and we shape the conditions faced by those who follow. This capacity allows us to anticipate possible futures — not with certainty, but with responsibility.

As ecological knowledge has deepened, it has become harder to claim neutrality. When evidence suggests that actions may affect living systems in ways that are persistent or difficult to reverse, choosing not to engage with those implications becomes a decision in itself.

The Green Imperative does not demand perfection, nor does it remove complexity or trade-offs. Food production, land management, and public infrastructure all involve competing needs. What changes is the frame: success is no longer measured only by short-term effectiveness, but by how decisions sit within the longer arc of ecological and human wellbeing.

This is the point where ecology and ethics meet — not in certainty, but in care.

Not in blame, but in foresight.“When we know better, we should do better.”

Small Shifts, Living Systems

When discussions turn toward ecology and ethics, it can be easy to feel overwhelmed. Large systems, global pressures, and long time horizons can make individual choices feel insignificant. This is where perspective matters.

Living systems rarely change all at once. They respond to small shifts, applied consistently over time.

For gardeners, growers, and land managers, this does not require perfection or wholesale change. It begins with attention.

One simple shift is observation before intervention. Weeds, for example, are often treated as enemies to be eliminated. Yet many act as indicators — revealing soil compaction, nutrient imbalance, moisture stress, or disturbance. Responding to what the land is signalling can sometimes reduce the need for repeated control altogether.

Another shift is prioritising soil cover. Bare soil is a stressed system. Mulch, living ground cover, and organic matter protect microbial life, moderate temperature and moisture, and support resilience. Healthy soils tend to resist invasion more effectively than depleted ones.

Where scale allows, mechanical or manual control can replace chemical intervention, especially when used early and consistently. This is not always practical everywhere, but even partial substitution can reduce overall reliance.

Timing also matters. Addressing issues when plants are young, soil is moist, or pressure is low often prevents escalation later. Many problems become chemical problems only after other options have been delayed or overlooked.

Finally, there is value in accepting some level of disorder. Uniformity may look tidy, but diversity tends to be more stable. Allowing space for variation — in plants, insects, and soil life — supports systems that are better able to adapt over time.

None of these shifts deny the realities of modern land use. They simply widen the range of responses available. Rather than asking whether a tool works, they ask how its use fits within the larger system, and whether gentler options might meet the same need.

Small changes, applied thoughtfully, often have larger effects than expected — especially when they align with how living systems actually function.

A Relational Way of Deciding

In te ao Māori, the natural world is not viewed as a collection of resources, but as a network of relationships. Land, water, plants, animals, and people are understood to exist within a shared system of whakapapa — a living genealogy that binds all things together.

One expression of this worldview is captured in the whakataukī:

Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au.

I am the river, and the river is me.This is not metaphor in the Western sense. It is a statement of relationship and responsibility. When the river is harmed, the people are harmed. When the people are well, the river is well. There is no meaningful separation.

Applied to decision-making, this way of seeing shifts the question. Instead of asking only whether an action is effective or efficient, it asks how that action sits within the wider web of relationships — across time, place, and life. Harm is no longer abstract or external. It is relational.

This perspective does not reject tools, science, or modern systems. Rather, it places them within a framework of accountability. Decisions are weighed not only for their immediate outcome, but for how they affect the health of the whole — land, water, communities, and those yet to come.

In this way, the Māori worldview offers not a rulebook, but a lens. It reminds us that choices made on the land do not end at the fence line, nor at the end of a growing season. They continue outward and forward, carried through living systems.

Seen through this lens, the questions surrounding glyphosate are not only technical. They are relational. They ask how we understand ourselves in connection to soil, water, food, and future generations — and how that understanding shapes what we consider acceptable risk.

This is not about arriving at a single answer. It is about choosing how we decide.

In Brief

(Summary for busy readers)

Soil is a living, dynamic system, shaped by biological communities, history, and past management.

Chemical use in gardens and landscapes can leave lasting legacies in soil that influence soil life and plant health over time.

Soil legacies are not just physical or chemical residues — they can alter how soil biological communities form and function.

Problems seen in the garden (like poor structure, imbalance, or pest pressure) often reflect historical soil conditions and past interventions, not only current practices.

Observing weeds, soil texture, and plant performance can help reveal underlying signals from the soil’s past.

Practices that build soil cover, organic matter, and microbial diversity help soil systems become more resilient and productive.

Working with living soil — rather than relying solely on chemical fixes — supports long-term health, balance, and ecological function

If You'd Like to Go Deeper

This reflection only touches the surface of much wider conversations about land use, chemicals, and living systems.

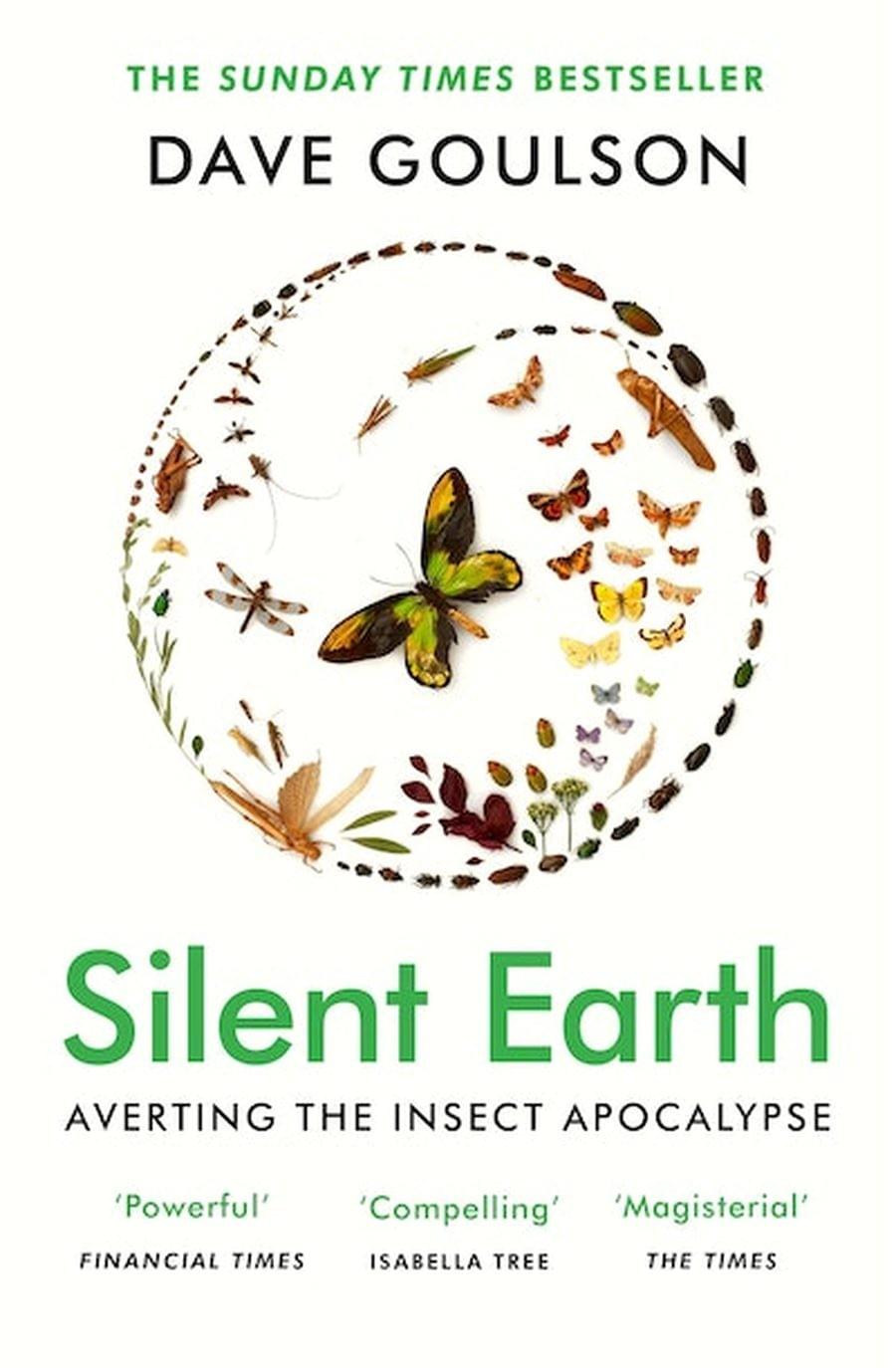

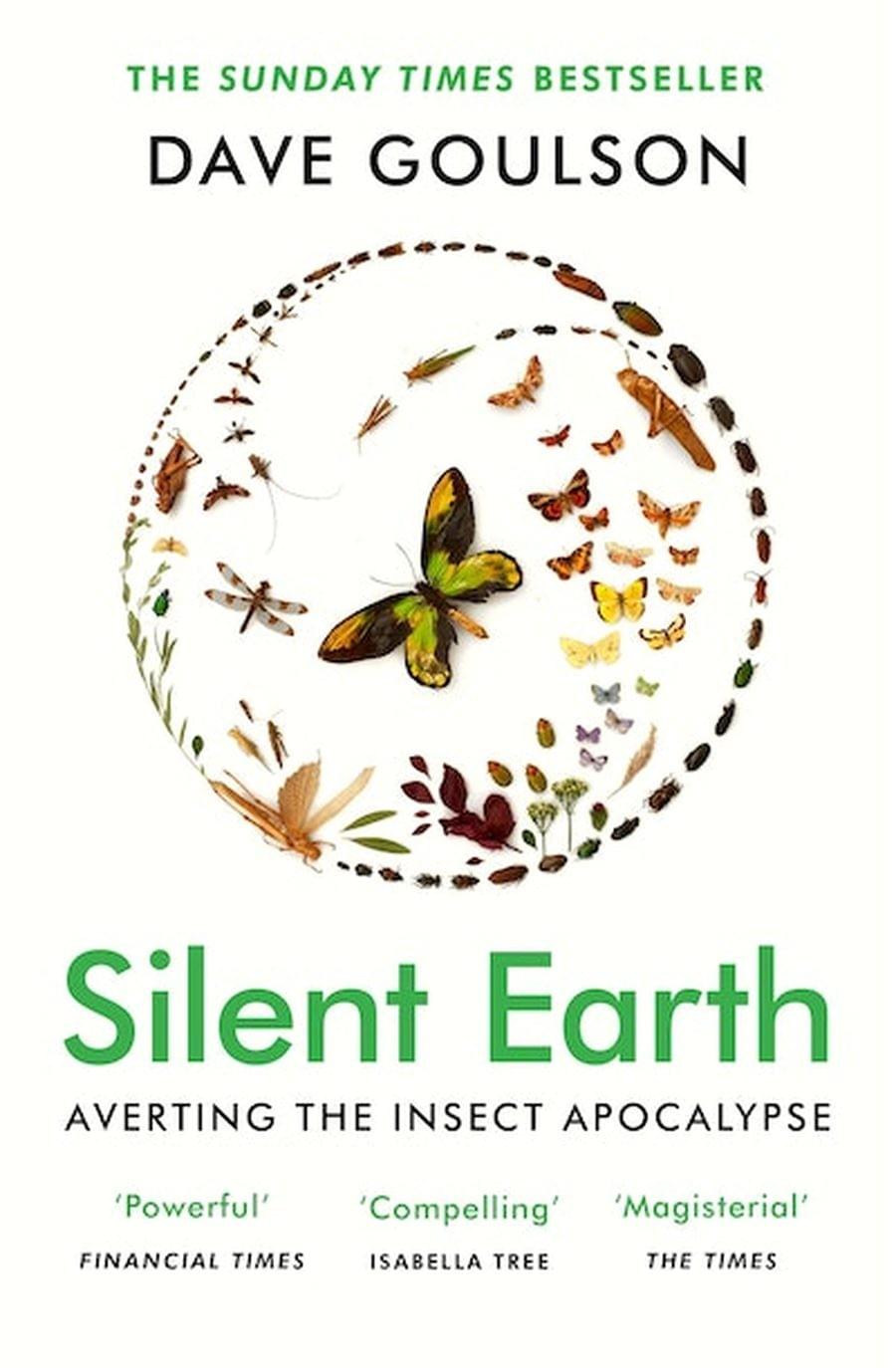

If you’re interested in exploring these themes further — particularly the quieter, less visible impacts on ecosystems — Silent Earth by Dave Goulson is a thoughtful place to begin.

The book examines the decline of insects and other small life forms that underpin soil health, pollination, and food systems, and considers how modern agriculture and chemical use interact over time.

It is not a call to alarm, but a call to attention — inviting readers to notice what often goes unseen, and to consider how small decisions accumulate into large consequences.

© 2025 Tomato Love | Epic Tomato Source for heirloom seeds and seedlings grown in Hokianga. Cultivated with love, history, and mana.

“He iti, he pounamu.”